The Focusrite Guide To Releasing Music: Part 2

In the first part of this four-part series, I talked about how to ready your songs for release, including the necessary steps to get a proper mix and final master that will sound great on streaming services and on physical music products like CDs or vinyl. (Check it out here.)

In this second part, I’ll cover two main tasks a musician should tackle once their music is mixed, but before it is actually released as a digital or physical product. First, I’ll talk about protecting your original songs from being duplicated or sampled by other artists, through copyright registration. Secondly, deciding between a self-release plan or working with an independent record label to get your music out there. This includes discovering labels, pitching them, and negotiating a deal.

I’ll caveat this section with a quick reality check: there are so many ways to approach this, so many different tools to reach the same goal, and a multitude of different opinions offered from one expert to another. My perspective is generally one of self-protection, so I tend to advise being extra careful when it comes to protecting your music and livelihood. So, as ever, I urge you to take this advice and build on it. There are plenty of links throughout this piece to help you discover more on the topic. I’ll also add that my advice here comes from a US perspective. If you live outside the US, I advise you to research your local laws to gain as much knowledge about your rights in your part of the world. The more knowledge you have on this complex world of copyright, the better — it’ll help you choose your own path to a place where you’re on good legal ground, in a good relationship with your releasing partners, and happy that people are hearing (and paying for!) your music.

Also, regarding copyright: I am making the assumption that your songs are 100% original compositions written by you and / or your bandmates or co-producers. If you have used samples of other songs in your own, you won’t be able to copyright the song as an original work, and the process of getting a copyright for what is called a ‘derivative work’ is much harder.

Why is copyright important?

Technically once you have recorded a song, and burned a CD of it or put it on any other physical device — like a USB drive — your work is copyrighted, but the copyright needs to be registered with an official office. Registering your copyright will protect your songs — the music and the lyrics — from being duplicated or sampled by other artists. If another artist covers your song, samples it, or replicates it any other way without your permission and you have secured the copyrights, then you have legal recourse against them up to $150,000 per wilful infringement. You can only file a lawsuit if you have registered with the U.S. Copyright Office and they have made a final ruling on your application.

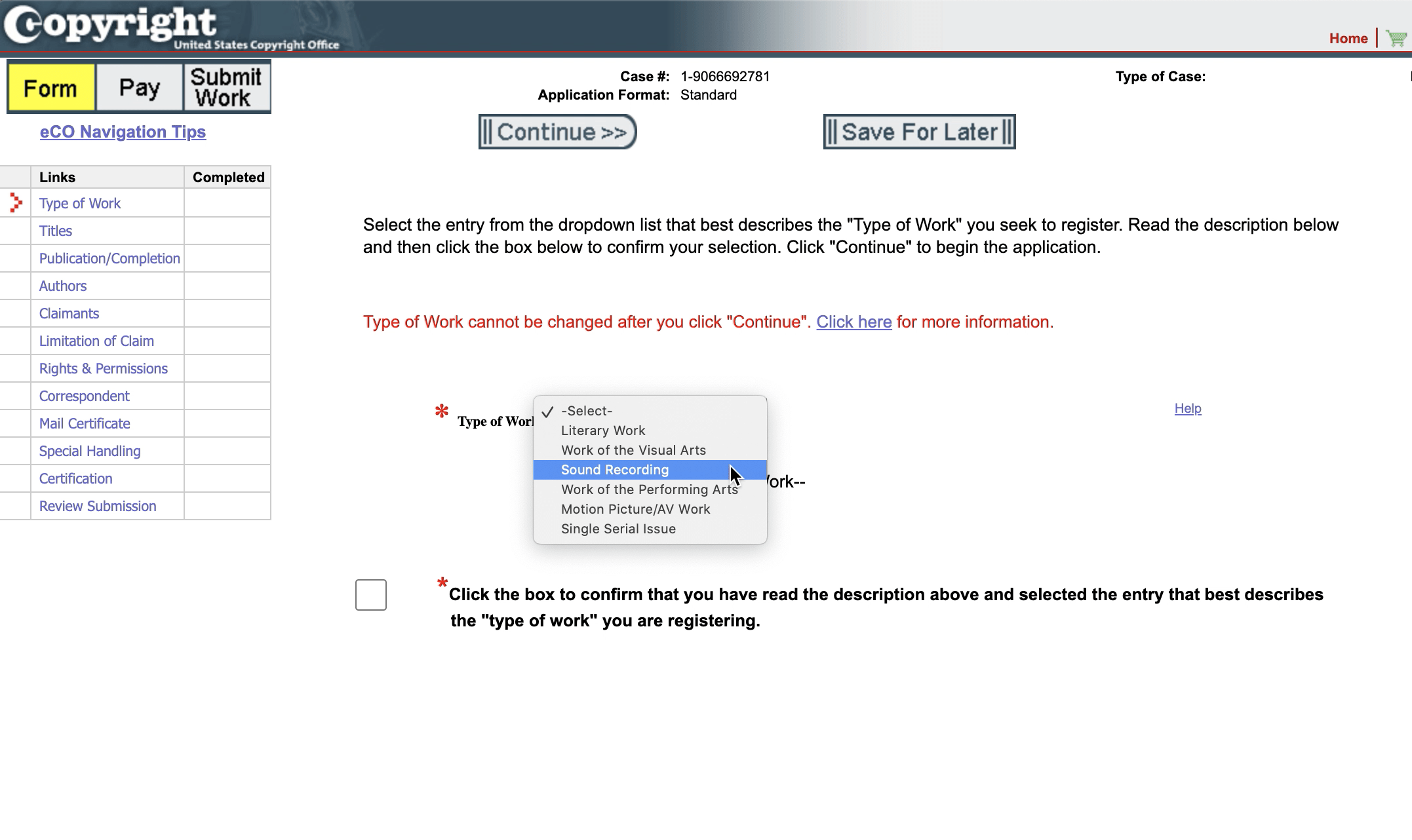

A screenshot from a section of the US Copyright Office website where Sound Recordings are registered.

No matter where in the world you live, it’s best to register with the US Copyright Office, as most countries across the world will recognise a song copyright registered in the US and offer protections for the copyright owner. There are lots of complications that can arise when filing a song copyright: your application could be declined, and even if approved it can take anywhere from three to seven months to receive your copyright certificates. It costs about $45-$65 per song for each application and you may wonder if it is worth that price when it would take about 14,000+ Spotify streams of that song to earn the fee back. My take is that it’s definitely worth it because, for goodness sakes, what if one of your songs is discovered by a larger artist, is sampled or re-recorded and becomes a major hit. I have seen this happen so many times. At the start of 2020, rapper Lil Nas X was hit by a copyright infringement lawsuit by a younger upstart rap duo PuertoReefa & Sakrite Duexe, who recorded a very similar sounding track three years earlier. I don’t know the ins and outs of this case, but if the duo registered the copyright for their song, then they would be able to go to court quickly to file a lawsuit immediately and would not have to wait months to make a move.

The US Copyright Office and the various copyrights they issue are very complicated to follow. Cosynd (https://www.cosynd.com) is a great service for musicians looking to navigate the complexity. For $30 fee on top of the federal copyright filing fees, Cosynd’s registration service includes the preparation, review, e-filing, and handling of correspondence with the US Copyright Office as needed for the life of the application (three to seven months). Once you have submitted your application to Cosynd, it is reviewed, checked for potential errors, and a determination about the final application type that should be used for your filing is made. Cosynd also offers other song ownership services, including the ability to create, negotiate, and sign vital copyright-related agreements with your collaborators that establish your ownership.

Do I really need to copyright my songs?

I have been producing music for 25 years. The fees and forms were a bit easier to follow in 1996 when my first album was released; since then, the complexity in copyright applications has grown exponentially. There are also so many more ways your songs can be infringed on by others, whether it’s unauthorised use in a YouTube video, a social platform like TikTok, by sampling, etc. In more recent years I have been successful with my music efforts, releasing tracks, EPs and albums with well-regarded independent record labels. So I became more interested in protecting my songs, but the answers I got about copyright were murky. Even my entertainment attorney advised me that — because I am publishing my songs through publishing companies owned by the record labels or on my own with my publisher, Funk Style Quality Music (BMI) — I did not need to file copyrights. This is not correct, artists should protect their songs by filing for copyrights. Some music industry professionals give the impression that you are protecting your work via music publishing, but read the fine print closely. For instance, Songtrust, a music rights platform for independent publishers, writes that “the act of registering your songs with Songtrust is a great alternative to prove active ownership of your catalog without going through the US Copyright Office.”

Independent digital music distributors Distrokid and Tunecore add a bit more to the confusion a bit more, mentioning that just having digital distribution is enough for you to have copyrights for your songs. At the time of writing this piece, I understand copyright professionals are actively working to make sure musicians do not get the wrong impression from such statements. While it may be true you own your music by its mere creation and distribution, you still need to legally protect the songs via registered, government-approved copyrights. Meanwhile distributor CD Baby partnered with Cosynd to offer musicians an avenue towards copyrighting their music while also distributing it via their platform.

Liz Cimarelli, COO and Head of Business Development at Cosynd clarifies why copyright is needed beyond publishing music: “Think of registering with the Copyright Office as a form of insurance. You hope that nothing happens, but if it does, you won't be able to do anything about it if you don't have it registered (and approved) by the Copyright Office beforehand.”

Cosynd and CD Baby have joined forces to make protecting content easier than ever.

Sampling and covers

My advice is to avoid sampling at all costs because of the legal clearances you’ll need to get from the publisher and owner of the master recording of the song you sample. If there are really elements of particular songs you would like to sample, I would look to see if any of these songs you want to sample are pre-cleared on the sample licensing platform Tracklib which has thousands of entries. Or maybe you can find the specific sounds you are looking for on the sample library sites like Splice. One of the members of my group FSQ, G Koop, is known as ‘the sample replay king’ meaning that instead of sampling, he will actually pick up instruments and make a new recording of an old song. If there’s a riff you really want to add to your song, rather than sample the master recording, you can get musicians like G Koop to recreate and replay the music, the riff, the hook, essentially you desire to add to your song. You will still need to reach out to the publisher of the song to get permission to release your song with the elements (the replays) of another song included.

Getting a license to release your cover version of an original song is a bit easier than licensing small components of another song. The process of licensing cover songs is made easier through platforms like Easy Song Licensing and Soundrop, which charges a one time flat fee of $9.99 per cover song license. Soundrop also is great about dealing with the licensing of cover versions for YouTube, which are a big part of many YouTube video creators' repertoire. Tunecore and Distrokid, mentioned earlier, also offer licenses for cover songs starting at about $15 per year if an artist expects less than 500 digital downloads of their cover.

To sign with a record label or not?

I’m primarily talking about signing your songs — whether it be a single (two songs), EP (four to six songs) or album (eight or more songs) — with an independent record label. Independent record labels can be great to work with because they can amplify your release plan with a real investment and their own existing distribution and press networks. Some record labels are known as being curators of quality artists and particular genres, with real fans consuming all the output of the label. The ability to plug into an audience you don’t already have is a tremendous addition to your release plan. There are two hurdles to get over in terms of signing with an independent record label. One, is actually finding one that would be interested in your songs, and two is getting the label to present you with deal terms that would actually make it worth your while to sign a record release deal.

Even if you find your ideal suitor, you still need to advocate for yourself and make sure your music is protected before sharing it. I urged you in this column to first protect your songs by registering them with the US copyright office. If you have applied for your copyrights, you should feel comfortable pitching your music to record labels, because you would have legal recourse against a label if they somehow commit theft and release your music without your consent. One other technique is to upload your songs to SoundCloud, make the uploads private and send them to labels you are pitching versus sending the final masters. One consideration is that you may lose some of your audio quality by hosting your songs on a streaming service instead of sending full-resolution audio. And you want to put your best quality output with the label you’re pitching.

Finding and pitching with an independent record label

There is no singular best practice for pitching your music to labels, but the golden rule (as with everything on this topic) is that the more you experience, the better informed you will be. There are many strategies for pitching. Whatever your approach, building a relationship with prospective partners is always encouraged. After you have personal experience with people at independent record labels, and/or specifically pitched them your music, you will have an initial idea of what opportunities lie ahead for you in terms of releasing your music with a record label, and whether you want them as your release partner.

If you typically produce music within a specific genre, you’ll probably know artists who are similar to your sound and the record labels that release such artists. Unfortunately, lots of independent record labels hang out shingles saying ‘no demos please’. But many label bosses, especially in the world of dance music, are also DJs. Relationship building is key if there’s a label you have an affinity for. Jack Priest, a UK based producer, sent his music to Wolf + Lamb (W+L), which is both a DJ duo, Zev Eisenberg and Gadi Mizrahi, and also a record label run by the duo. Jack sent the music to W+L under the guise of “hey guys, please play my music when you DJ”. He wasn’t trying to persuade W+L to sign him as an artist, especially as they also had the ‘no demos’ alert on their website. He began sending them music in 2014, and eventually W+L released a bunch of his DJ mix edits. Then by 2019, they signed and released his original album Harry Had to Work. So it took five years of relationship-building between Jack and the label to get them to commit to releasing his album; persistence is key. Sometimes an artist’s music shines so bright that a label will rush to sign them. David Marston sent an EP of music via email to the dance music DJ duo Soul Clap, with no prior relationship with them. They released his The Jamaicalia EP within months of his first email.

Beyond aligning with labels that release the styles of music you like, you could consider finding organisations oriented around specific mission statements or artist identity. While they do not release records themselves, Discwoman is “a New York-based collective, booking agency, and event platform representing and showcasing cis women, trans women, and genderqueer talent in the electronic music community.” As the Discwoman slogan reminds us, alliances with like-minded groups help us “amplify each other”, and build networks.

Streaming platforms

Bandcamp and Soundcloud are great platforms to discover the catalogs of independent record labels if you are still searching for labels to pitch your music towards, and both platforms have direct messaging features if you are looking to get in touch. Jack Priest, who I mentioned earlier, also signed a record deal with Green Velvet’s Cajual Records via messaging them directly on SoundCloud. These platforms have become huge allies to independent music makers and labels, in large part due to the lack of support from major streaming services like Apple Music, Amazon Music, and Spotify, who have not done a good job of highlighting independent record labels as unique brands and curators of quality artists; there are very few features on those platforms that support record label showcases.

Streaming/commerce platform Bandcamp is especially attractive to independent labels, thanks to its showcase feature that acts like a homepage for a label.

There are also great organisations that collectively represent the independent labels. For instance in the US, there’s A2IM, in the UK, it’s AIM. Such organisations have member directories of the record labels participating, and this is another great place to discover potential avenues to get your music out there. Europe is broadly covered by a trade group called Independent Music Companies association, or IMPALA. Australia has AIR, the Australian Independent Record Label Association. Many nations' cultural funding programs incentivise local radio stations to play music by artists from that country, and for independent record labels it's very much the same approach. Therefore, if you are seeking an independent record label and you are from France, for instance, it makes sense to see what French record labels align with your sound. There are also music trade organisations that are focused around specific genres. One of the most well-organised is the Folk Alliance International. Becoming a member of such groups allows you to connect further with labels and artists producing and releasing music in those specialty areas.

Coming up in part 3...

In the next part of my series, you’ll learn what minimum terms to ask for in any potential deal with a record label. If you can’t come to an agreement on such terms, or have not found a record label to partner with, I will review the best options for self releasing your music, including how to compare and evaluate digital and physical music distributors which will deliver your music to streaming services and music retailers.

Whether you are with a record label or on your own for your upcoming EP or album, I will educate you about two of the most important aspects of the release process beyond mastering audio and registering copyrights. One is collecting and organising metadata related to your songs. Without this metadata properly handled, potential fans won’t be able to easily discover your music on streaming services. The second aspect focuses on publishing your songs with performance royalty organisations to ensure you are paid for the playback of your music on streaming services, radio, and a plethora of other media channels.