Raw passion inspires change in Malawi

In conversation with Chmba – a Malawi-based musician and DJ looking to empower and inspire a new generation.

The power of community and music when advocating for change against the status quo is undeniable. Throughout history, we have seen the role that music and community has played in challenging existing ideals. A similar shift for change is being made in Malawi, where Chmba, a producer and DJ, is making waves that can be felt across her community. Having self-produced and released her own music, she’s hoping to give marginalised identities within her community the same opportunities to thrive creatively and aspire greatness outside of their hometowns.

Chmba’s musical origins came very early on. “It wasn't necessarily a journey of finding it, rather just being born within it,” she says. “My parents were disco and electronic music fans, so I was born into a home full of music cassettes. My parents were still in college when they had me. I was definitely the baby at local discos, especially with my father and his brother operating the boombox. Soon, I found myself playing around with those cassettes after school, then making my own mixes through the old school way of chopping up the cassette tape and putting it back together with clear sealing tape.”

From these do-it-yourself origins, Chmba’s natural curiosity and affinity for music constantly grew. Chmba notes that the music scene in Malawi went through peaks and valleys as music technology adapted and changed, especially within the electronic music scene. “It’s a growing scene,” she says. “It disappeared in the last decade, with more mainstream music taking centre stage, the spread of TV, the influence of the media and the digital era. It certainly discouraged the old method of scouting for cassettes or listening to whatever record you would come across and discovering something new, which diversified tastes.”

That raw and physical connection to music is something that seems to resonate strongly with Chmba. Although, she is not averse to the progression of music and technology, and the potential it brings to music in Malawi.

“In the ‘80s and ‘90s, you had people copying and spreading a cassette of an unknown band from Namibia, a Fela Kuti cassette, something that came from Australia, or something from South Africa of Brenda Fassie. It was about hearing whatever was available, or what someone liked and recommended. Now, most people only listen to the Top 10s, or what’s popular and readily available. Spotify just came to Malawi in 2021, so it will be interesting to see how that will affect streaming and tastes. Already, my music is picking up more.”

Although the music scene in Malawi is certainly growing, there are still some attitudes within the industry that present prejudices towards women and gender minorities. “It’s a shocking attitude with underlying misogyny, but also just a lot of foreignness to it,” explains Chmba. “A lot of people admit that I’m the first female producer they have met. When I dropped my EP, some male producers would ask several clarifying questions like, ‘you actually produced this?’ or ‘are you sure?’. As though I didn’t understand what production actually meant.”

Being met with these confrontations hasn’t stopped Chmba, though. Much in the same way that she took music-making into her own hands at a young age, she has continued to forge her own musical path.

"Music is so central to who I am. It’s also a healing space for me.”

Chmba’s identity is tied to her music. “It’s so central to who I am, as I have made references describing a moment or how I am feeling my songs. It’s also a healing space for me. My first EP allowed me to truly grieve for my late mother when I couldn’t find the words. I make the chords for the feeling. Creating is somewhat my way of journaling.” Being able to use music as an outlet for personal expression has become an invaluable space for validation and affirmation of her identity. “As someone queer, the DJ and production spaces are sometimes the only spaces where I can be my full self in public. When I’m on stage, it’s no longer about ‘why is she dressed in a non-conforming way?’. It’s just about the art – the crowd is so focused on the music.”

While these moments of clarity in self-expression when performing are affirming and invigorating, they are not always met without confrontation. “I have also been abused in clubs and discriminated against. One time, I arrived at a venue as the next DJ and the DJ before me refused to leave the stage. They said there was no way that I was the next DJ, and continued playing into my set time, so I had to bring out the club manager.”

“Getting booked is also a challenge. All-male line-ups are almost all you see here, and sadly, most of the time, to get booked as a woman, the event manager is either romantically or sexually interested in you. Being queer, with very little women-led spaces, my chances of being booked are even slimmer. My first 30 gigs were outdoors, and I was only trusted to play them because I had ‘played in New York.’ Because I have a foreign element, I am respected. It’s sad. This is why I created our Feminist Sonic Space at Tiwale, a community-driven educational charity, also known as The Beats By Girlz Malawi chapter.

"It’s so important to create a space that affirms and advocates for female, nonbinary and queer artists.”

With such involvement in grass roots projects for the empowerment of women and the LGBTQ+ community, it is surprising that Chmba feels that her music is not necessarily tied to her activism. “It is tied to the human experience, which is based on lived oppression, and then becomes an expression of struggle, and thus activism.My song ‘Freedom’ is about the journey of searching for that sweet peace, the end goal for all of us. Activism is a necessity born because we have to work and fight for our freedom, and in a world of oppression, sometimes we have to beg for it, hence the repeated lyrics ‘beg for it’ in the song.”

With such involvement in grass roots projects for the empowerment of women and the LGBTQ+ community, it is surprising that Chmba feels that her music is not necessarily tied to her activism. “It is tied to the human experience, which is based on lived oppression, and then becomes an expression of struggle, and thus activism.My song ‘Freedom’ is about the journey of searching for that sweet peace, the end goal for all of us. Activism is a necessity born because we have to work and fight for our freedom, and in a world of oppression, sometimes we have to beg for it, hence the repeated lyrics ‘beg for it’ in the song.”

“I try to make sure my music is honest and raw in what we feel, and how we live. It is all very vulnerable. Being black, being queer, being a citizen of an African country – they all come with their own struggles, and as someone living them, my songs will bring them up.”

A community-driven push for change

For Chmba, enabling those in her community to aim for and achieve their aspirations is one of the core drivers of her activism. Tiwale, Chmba's community driven educational charity, was formed in June 2012 as a pilot Summer project, targeted at finding creative entrepreneurial solutions to help keep women and girls in school. “In 2012, child marriage was still legal in Malawi – it was only criminalised in 2018,” explains Chmba. “This created a cyclical pattern of generations of young women dropping out of school at secondary school level. Factors encouraging this included the education fee imposed by the government for secondary schooling, and with child marriage being legal, many families believed girls aged 13 to 16 – which is the secondary education entry age – might as well marry as they can’t afford the fee.”

Despite child marriage since being criminalised, Chmba says many people still drop out at secondary school level. “As this has been a challenge for years, many people under 30 years old have very basic education, are unemployed, and living in poverty. The situation is worse for young women and minority identities, such as the LGBTQ+ community.”

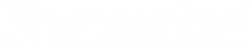

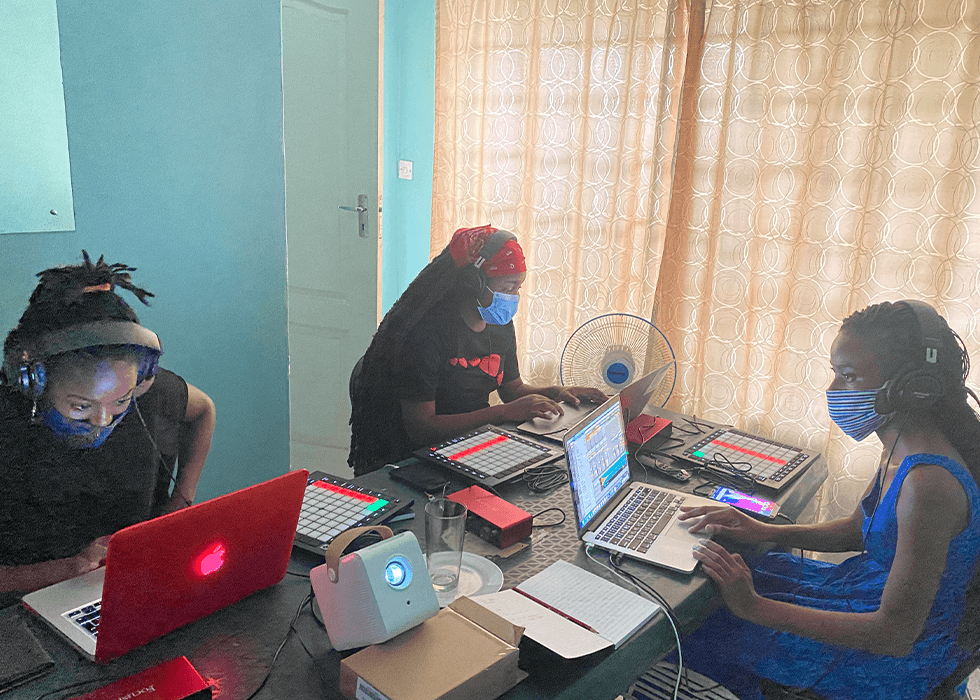

In the time since its conception, Tiwale has established community learning spaces that provide better opportunities for women, girls, and LGBTQ+ people, with a focus on women and girls aged 13 to 30. These programs include primary and secondary school classes, digital literacy and STEM, music technology, sewing and fashion design, community libraries, sanitary pad-making classes, as well as mental health-focused circles and gatherings. “Each program duration is one year, although some classes such as sewing can go up to 1.5 years,” Chmba elaborates. “The programs are also followed by micro-loan or scholarship opportunities that enable participants to venture out and sustain themselves using the skills they’ve obtained. We are a team of 12 – nine of which are under 30 years old, two are graduates of Tiwale who lead some of the workshops, and two are volunteers.”

Having worked with a community of 396 women and girls across various programs and workshops, Tiwale has undoubtedly made a significant impact, making Tiwale’s students and alumni a cause for celebration. “Our impact is assessed through the growth in their positionality, their access, influence, skills and income. For example, our 40 micro-loan program participants have thriving businesses; one just bought a car, one started a pre-school, 12 are landowners, and each one has their children enrolled in school.”

Seeing the work of the organisation coming to fruition in the shape of women, girls, and members of the LGBTQ+ community achieving what was once not thought possible is an encouraging push in the right direction. All this works in an effort to change the existing statistics of representation in the music industry in Malawi.

“A survey conducted on 651 music producers, found that less than 2% of the producers were women. Women make up 21.7% of artists, 12.3% of songwriters, and 2.1% of producers,” explains Chmba. “Women and other marginalized identities such as the LGBTQ+ community and people with disabilities face overwhelming discrimination and reduced access to education and resources, platforms, events, and opportunities within music and music tech. Across Africa, this is no different. It is more severe with a serious lack in action to build music opportunities for these disadvantaged people. Our Feminist Sonic Space is a free DJ and music production skills fellowship workshop. Occurring annually, it allows more women and non-binary people to gain access to the music industry.”

Raising the voices of silenced communities in Malawi

Globally, the fight for equality and acceptance of marginalised identities is a work in progress and being a member of the LGBTQ+ community in Malawi poses many difficulties. “The LGBTQ+ community lives underground here,” says Chmba. “Most people are not vocally out, considering the risks. It is illegal to participate in homosexual activity in Malawi and so a lot of us live as though we do not have lovers.”

“My wardrobe definitely changes by where I’m going. As someone who prefers androgynous clothing, I certainly can’t look ‘too gay’ in some places as it’s dangerous. However, interestingly enough, a lot of people don’t know what queer is or what it looks like.”

With such severe societal pressure, the inability to express one’s true identity or even have a space to figure out what that might be can be detrimental to mental and personal growth. This is why Chmba’s work with Tiwale and Beats By Girlz Malawi – also known as Feminist Sonic Space – is of such importance.

“Beats By Girlz seeks to encourage the musical dreams of young women and LGBTQ+ folks in the country by providing a safe learning environment. The hope is for our students to thrive and shake up the music scene here in Malawi and across Africa by breaking the existing dominance of cis-gendered heteronormative male figures in the industry. We hope for this to also bring new employment and income growth opportunities.”

By providing marginalised identities with safe spaces to explore themselves and gain access to otherwise prohibited fields, Chmba and her community are actively changing the lives of many, as well as their perceptions of what they thought possible for themselves.

“I want to keep building up Tiwale as a space to better serve marginalized identities and the community through learning access. I dream of a future where our classes have expanded to something more formalized with legitimate certification. I dream of us hosting exchange residencies with artists around the world, diving deep with our classes to a fuller breadth of sonic creation and understanding. Our first scholar just got into university, so I hope for more of that. More testimonials of growth at our spaces.”

As for the future, Chmba hopes to remove the perception of otherness from African music, and have it seen as equal among existing genres. “I wish the space could become more diverse, so that there would be a better understanding that electronic music is everywhere. For people to understand that a song from Mali or Malawi can be Indie, Rock or R’n’B, and shouldn’t only be labelled as ‘World Music’ or ‘Global.’”

Chmba voices her concerns about the music industry’s inaccessibility. “You gain access to the industry through who you know and connections,” she states, “access is full of gatekeepers.” However, through her community endeavours, Chmba is bringing the passion she so strongly desires back to music in Malawi and opening doors for others to step into that light along with her. “I wish the music space could go back to being about raw curiosity, raw passion and talent,” she says.

“I HOPE FOR MY MUSIC TO REACH THE WORLD, AND I WANT MY SONGS TO BE TIED TO PEOPLE’S LIVES AND MEMORIES, AS MY SONGS ARE A SERIES OF EMOTIONS AND I HOPE THAT SOMEONE OUT THERE CAN RELATE.”

WORDS: ZAINAB HASSAN